Hydropower has historically been one of the most important sources of energy in Alberta. Some of the earliest power stations in the province were hydroelectric plants, and by the 1950s, most of the province’s electricity came from rivers. Hydropower began to develop actively in the early 20th century to meet the dynamic province’s energy needs. The first large-scale hydroelectric plant in the province was the Horseshoe Plant. Read on at calgary-name to learn more about the history leading up to its construction, the building of the hydroelectric plant, and what followed. More on calgary-name.com.

Background

The first commercial-scale hydroelectric power station in the world was opened in Appleton, Wisconsin, in 1882. By 1890, the United States had at least 200 hydroelectric plants. Neighboring Canada, rich in powerful water resources, quickly took up the development of this industry.

Ontario and Quebec led the way due to their proximity to rivers in the Hudson Bay Basin. In Alberta, the development of hydroelectric power was a direct result of the immigration program to the province in the early 20th century. The rapid population growth created a significant demand for electricity. The most substantial growth was observed in Calgary. This factor, combined with the proximity to the Rocky Mountains, made Calgary the epicenter of hydroelectric development in the province.

The first hydroelectric plant in Calgary was far from the typical megaprojects of the 20th and 21st centuries. It was a small facility built by the Calgary Water Power Company in 1893. Initially, the hydroelectric plant worked as a supplement to the company’s steam-powered station and was later connected to a generator that provided electricity to much of Calgary for 10 years.

Horseshoe Plant

By 1905, it became clear that the small hydroelectric plant could not meet the needs of the growing city. Moreover, the simple structure was unreliable: in winter, the water system would freeze, and spring floods threatened to wash the station away. As a result, two Calgary entrepreneurs, W.M. Alexander and W.J. Budd, established the Calgary Power and Transmission Company in 1907 to build a large hydroelectric plant on the Bow River, near Horseshoe Falls.

The area around Horseshoe Falls was an ideal location, but the men greatly underestimated the engineering challenges and the cost of the project. They had signed a contract to supply Calgary with electricity by 1909, but they were unable to complete the hydroelectric plant in time. At this point, financier Max Aitken intervened and purchased the entrepreneurs’ company, which he renamed Calgary Power (which became TransAlta Utilities in 1981).

Max Aitken was one of the most prominent, decisive, and controversial figures in Canadian business history. He began his career in New Brunswick, achieved early success in Halifax, and truly made his fortune in Montreal, which was then Canada’s financial capital. Aitken had a visionary approach to business opportunities and risk assessment. He had a simple yet effective business plan: to control all the best hydro facilities on the Bow River and dominate Calgary’s power supply. Through this, he aimed to gain influence over Alberta’s future economy and secure cheap electricity for his factories.

The construction of the Horseshoe Plant faced many obstacles – floods, accidents, and a smallpox outbreak. The construction process was slow, but by May 21, 1911, the first large-scale hydroelectric plant in the province was completed. At that time, it had the highest capacity in Alberta. The city of Calgary, the town of Cochrane, and the Exshaw cement plant became the first consumers of the electricity it generated.

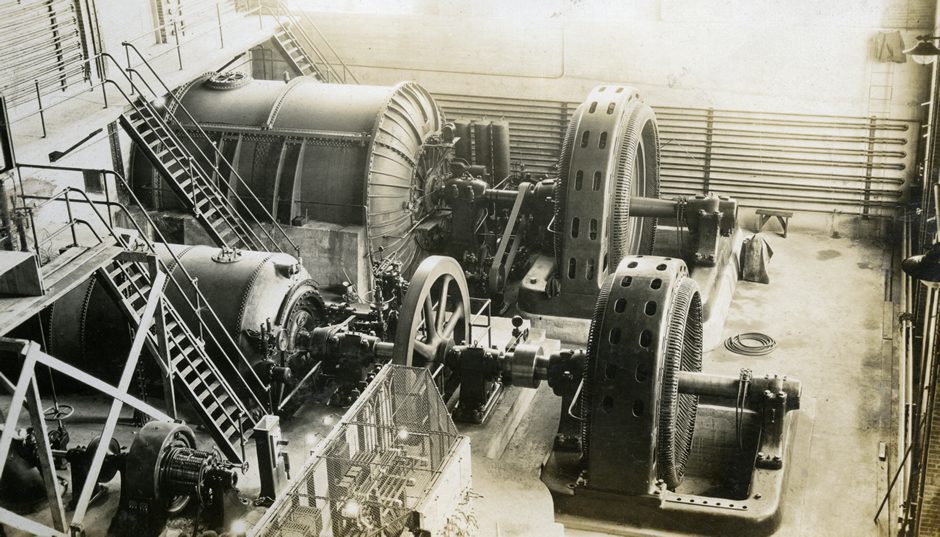

Four horizontal turbines provided a maximum capacity of 14,000 kilowatts. Later, four more turbines were added on the Bow River watershed, and the plant became a reliable power supplier for the province for the next 100 years.

In 1951, the local management of the Horseshoe Plant, with a 14 MW capacity, was replaced with a modern hydro control center, which managed five other hydro facilities. Through an automated system, the staff was reduced from 47 to 19 people.

This hydroelectric plant became the first step in a series of hydrotechnical developments aimed at providing reliable, environmentally clean electricity for the needs of the province.

The Settlement Near the Hydro Plant

Immediately after the construction of the plant began, a settlement called Sibe emerged at the confluence of the Bow and Kananaskis Rivers (the name “Sibe” is derived from Cree, meaning “stream,” “river,” or “meeting of waters”).

Over time, Sibe grew to include 22 houses, a residential complex with 17 apartments, a baseball field, and the world’s smallest ice skating rink. By 1914, the settlement had a population of 350. It had a small school for grades 1-6, which also served as a community center. Weddings, dances, plays, and other events were held at the school and the neighboring community hall.

By 1924, the population had decreased to 40 people, and by the 1990s, it had dwindled further. The school was closed in 1996, and the settlement itself was closed in 2004.

New Hydroelectric Plants and Dams

Even before the completion of the Horseshoe Plant, it became apparent that this project alone would not meet Calgary’s electricity needs. Therefore, in 1910, Calgary Power won a tender to build another hydroelectric plant on the Bow River, near Kananaskis Falls.

This project was delayed due to a dispute between Calgary Power and the Nakoda First Nation over which reserve the facility should be built on. The nation requested a one-time payment of $10,000 and an annual rent of $1,500 from the company for the right to build and operate the facility. Calgary Power accepted these terms and later obtained permission from the government. By 1913, the project for the second hydroelectric plant was ready.

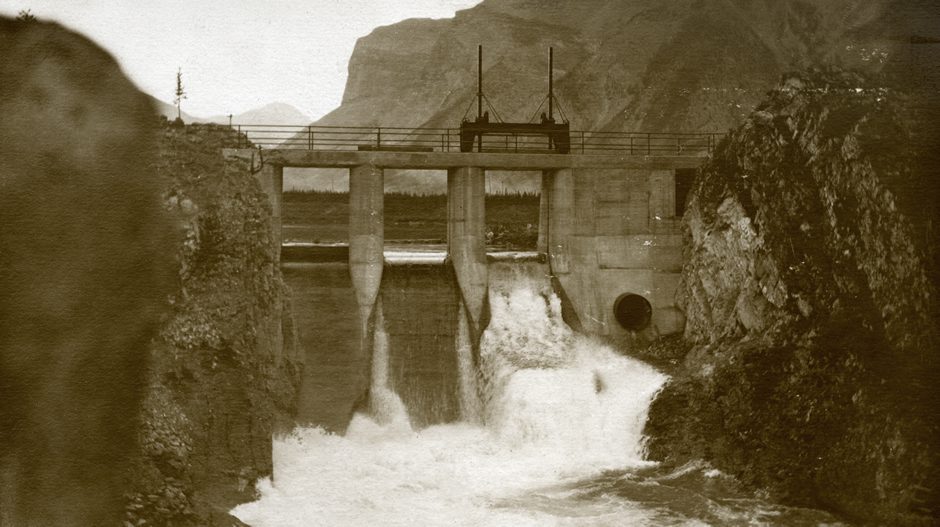

However, before its completion, Calgary’s engineers had an important task: solving the problem of irregular water flow on the Bow River. The best solution was to build a dam and reservoir to divert and store water. In 1912, a dam was built on Lake Minnewanka, creating a reservoir that partially regulated the river.

Post-World War Developments

After World War I, the demand for hydroelectric power greatly increased, leading to the creation of Alberta’s largest hydroelectric project in history – the Ghost Hydroelectric Dam. This plant was planned to be located on the Bow River, downstream from Horseshoe and Kananaskis Falls. An artificial lake was created for the station’s needs. This massive reservoir allowed for the regulation of water flow, providing adequate supply for existing hydroelectric stations and doubling Calgary Power’s production capacity.

Construction of the Ghost Hydroelectric Dam was completed in 1929, just before the Great Depression. During the crisis, all energy development projects were halted and remained inactive until the start of World War II. The war led to an increase in demand for electricity. In 1942, Calgary Power received permission to build a dam on the Cascade River, providing the necessary energy for military production.

What Happened Next?

By 1947, Calgary Power completed the construction of the barrier generator station on the Kananaskis River. It was the first hydroelectric plant with remote control in the province.

Subsequently, three new dam projects were introduced along the North Saskatchewan River and its tributaries. In 1954, Calgary Power built another hydroelectric plant, Bearspaw, west of Calgary. The following year, several more dams and hydroelectric plants were completed on the Kananaskis River.

Bearspaw Hydroelectric Plant

By the end of the 1950s, there were almost no remaining sites for hydroelectric plants. At the same time, the production of electricity from fossil fuels began to grow rapidly. In 1963, a dam and reservoir were built on the Brazeau River, a tributary of the North Saskatchewan.

However, by the early 1950s, nearly half of the province’s installed capacity came from hydroelectric plants, but over time, the importance of hydroelectric power gradually declined in the province’s energy landscape.