Even before recorded history, Indigenous peoples traveled through coal-rich regions near the Bow River Valley and Crowsnest Pass. They discovered coal deposits at the base of Mount Rundle near Canmore and along Cascade Mountain in Banff National Park. Early tribes also encountered layered coal seams in the arid areas of modern-day Drumheller. Although their use of coal was limited compared to European settlers, the early maps created by tribal leaders significantly contributed to the development of Alberta’s coal industry. More details can be found on calgary-name.

Taboos and Superstitions About Coal

The first recorded mention of Alberta’s coal seams dates back to 1793. Peter Fidler, a surveyor and cartographer for Hudson’s Bay Company, documented seeing coal near the Red Deer River at Nighills Creek, close to modern Drumheller.

Fidler also noted an interesting cultural feature: Indigenous peoples were aware that coal could be used as fuel but had deeply ingrained taboos against burning it. This prohibition stemmed from an incident where several families died in their sleep due to carbon monoxide poisoning.

There were other prohibitions and superstitions as well. Coal was not used for cooking as its smoke was believed to alter the taste of food. Indigenous groups in Alberta also associated coal with spirits of death. At the same time, coal was used creatively for drawing on rocks and animal hides.

The First Commercial Mine

Beginning in the mid-1890s, the Canadian government launched an aggressive campaign to encourage immigration to the prairies. Adult males could claim 160 acres of land in exchange for a $10 fee and a promise to develop agriculture, build homes, and live in the area for at least three years. This program was highly successful, increasing Alberta’s population from 73,022 in 1901 to 374,295 in 1911.

In the 1860s, prospectors from Montana arrived in southern Alberta in search of gold. They did not find gold but discovered coal deposits along the Belly River. Southern Alberta became a magnet for entrepreneurial enthusiasts. In the early 1870s, Nicholas Sheran arrived at Fort Whoop-Up and initiated the creation of a mine along the Belly River near modern-day Lethbridge. This became Alberta’s first commercial coal mine.

At the early stages of Alberta’s coal industry, mining varied in safety. Initially, coal was extracted manually. It wasn’t until the 1880s that mechanical cutters began to be introduced in some mines.

Steam Engines and Railway Expansion

In 1883, the first Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) coal-powered locomotive arrived in Medicine Hat, marking a significant change in the coal industry. Until then, horses, boats, and human power had been used for transportation. Steam power opened up a new world of possibilities.

The first branch line off CPR’s Alberta mainline was a 174-kilometre narrow-gauge track from Dunmore to Lethbridge. Railways set the pace for the coal industry’s development in the province and influenced the location of towns, as many were established near mines along railway lines. Over time, coal towns emerged across Alberta. Initially dominated by men, these communities began to see more women and children as the industry expanded.

By 1914, Alberta produced 27% of Canada’s coal output, with over 8,000 workers employed, most of whom worked underground. In the same year, a critical railway branch was built between Calgary and Drumheller, strengthening the industry’s presence in the Drumheller region and meeting Calgary’s heating needs. That year, the Lakeside Mine near Wabamun village also opened. By 1921, Alberta had been divided into 32 coal-mining districts.

Workers’ Struggles and Other Challenges

Rapid expansion brought challenges. Increasing production demands, hazardous working conditions, low wages, and other issues led to waves of strikes among miners. The federal government was forced to intervene in disputes between workers and employers. Eventually, Alberta’s coal miners received the highest wages in Canada, although strikes persisted.

The dangers of mining were evident in Canada’s deadliest mining disaster on June 19, 1914, at Hillcrest Collieries. After two days of downtime due to overproduction, 237 workers descended underground to resume operations. Only 46 emerged alive after explosions ripped through the mine.

The Decline of Coal and Its Resurgence

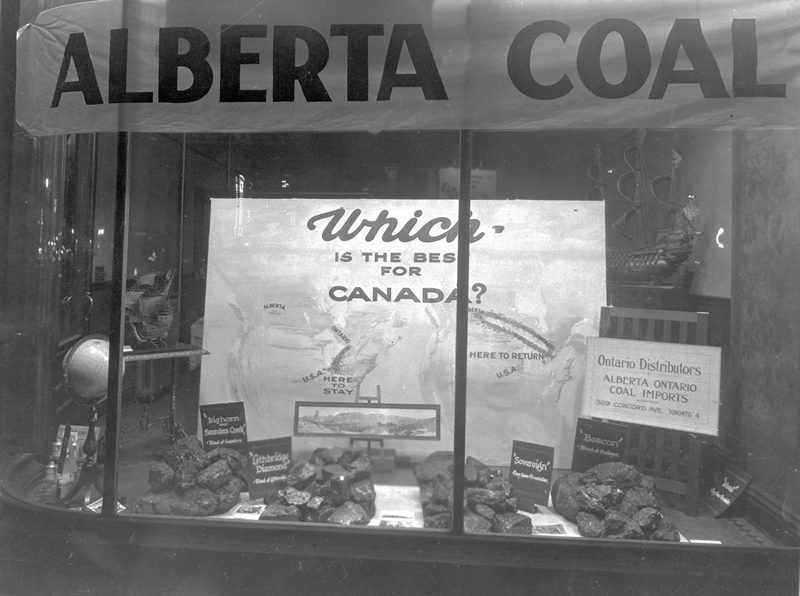

The discovery of large oil and natural gas reserves in Alberta in the mid-20th century marked the beginning of a decline for coal, as these resources offered economic advantages, higher efficiency, and easier usage. By 1961, coal production had dropped to 2,032,094 tonnes from a peak of 8,941,213 tonnes in 1946. Railways transitioned from coal-powered locomotives to diesel-electric engines, significantly reducing coal demand. Many mines shut down, and coal towns became virtually deserted.

Despite fears of the industry’s complete collapse, it recovered and continued to play a vital role in Alberta’s energy supply. Mines diversified by extracting other minerals and secured long-term contracts to supply local companies with energy. By 1962, coal production equaled the 1946 levels.

The Alberta government funded the construction of Alberta Resources Railway (ARR) near Hinton, operated by Canadian National Railway (CN). ARR transported coal from the Smoky River Valley to domestic and export markets. By 1994, ARR was fully owned by CN.

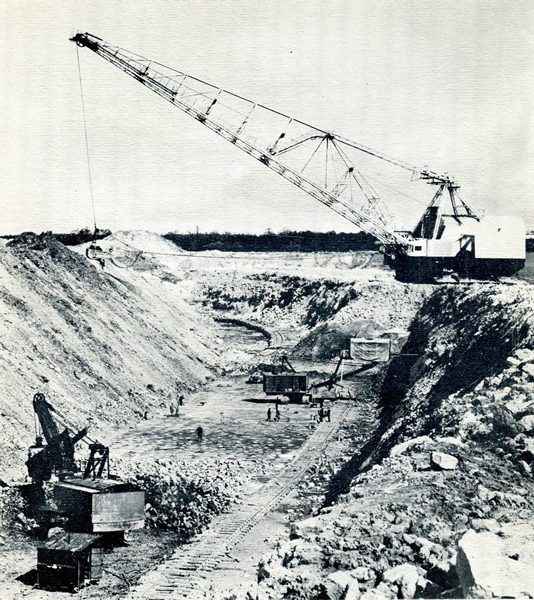

International markets played a crucial role in revitalizing the industry. Coal from Canmore and Crowsnest Pass was exported, particularly to Japanese clients. Alberta’s coal industry gained new life by transitioning to large-scale open-pit mining and expanding markets beyond the province.