The Canadian taiga hides some of the world’s largest oil reserves. The Athabasca oil sands, also known as the bituminous sands of Athabasca, are a mixture of silica sand, clay minerals, water, and large deposits of bitumen. Bitumen is a very thick and heavy form of crude oil (it is also called asphalt).

Only 20% of the oil sands lie near the surface, where they can be easily extracted. These deposits surround the Athabasca River, after which the oil sands are named. The rest of the sands are buried underground and are extracted by injecting hot water into wells, which thins the oil. More about the history of these deposits can be found below at calgary-name.

Discovered by Fur Traders

The first Europeans to learn about the oil sands in northern Alberta were fur traders in 1719, when a trader from the Cree nation named Wa-pa-su brought a sample of bituminous sands to the Hudson’s Bay Company’s factory – the oldest British fur trading corporation in North America.

The first European to see the deposits was another fur trader, Peter Pond, who founded the North West Company – a competitor of the Hudson’s Bay Company. He discovered the deposits in 1778.

In 1788, another fur trader, Alexander Mackenzie, while traveling to the Arctic and Pacific Oceans, noticed bitumen fountains near the Athabasca River, where a six-meter pole could be inserted. By then, it was known that bitumen mixed with spruce resin could be used to seal the canoes of indigenous peoples. Ten years later, the discovered bitumen began to be used by cartographer David Thompson, and in 1819, by British Navy officer John Franklin.

Scientific Study and Growing Popularity of the Deposits

In 1848, the oil sands were scientifically assessed for the first time. This was done by Scottish naturalist John Richardson while searching for the lost Franklin expedition.

In 1875, Canadian naturalist John Macoun began research funded by the government, and just eight years later, G. K. Hoffman of the Geological Survey of Canada successfully separated bitumen from oil sands using water. In 1888, Robert Bell, Director of the Geological Survey of Canada, informed the Senate committee that the valleys of the Athabasca and Mackenzie Rivers held the largest oil deposits in America, if not the world.

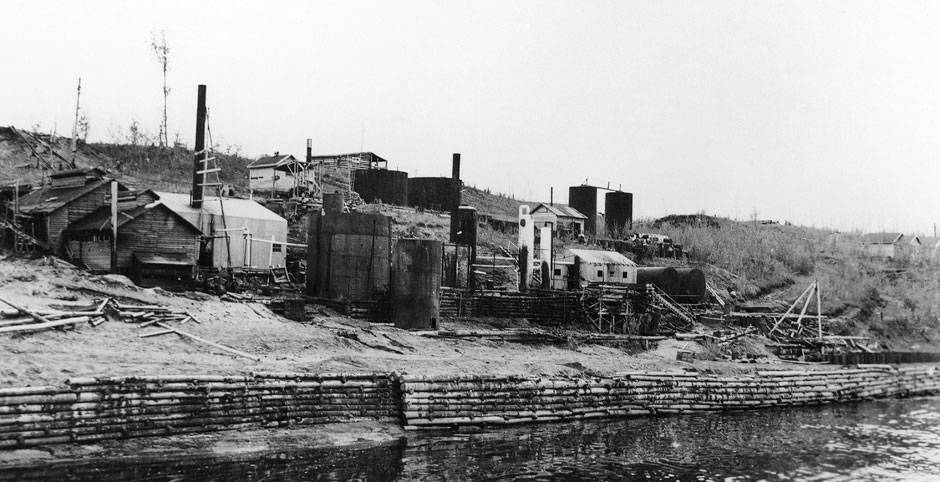

In 1897, Count Alfred von Hammerstein came to the region and spent forty years promoting the Athabasca oil sands, photographing the area. These photographs were later placed in the National Library of Canada and the National Archives of Canada.

Photographs of the oil sands were also included in the bestselling book by author Agnes Deane Cameron, who described her journey to the Arctic Ocean. After the publication of the book, the author traveled widely and gave lectures, showing the photographs she had taken. Agnes spoke with great enthusiasm about the Athabasca sands, and thanks to her book and presentations, she became a celebrity.

The Oilsand Project

In the 1920s, chemist Carl Clark discovered that bitumen could be easily separated from the sand using steam. In 1927, a corporation founded by Robert Fitzsimmons began extracting bitumen on an industrial scale using hot water injection into the sands. However, this method proved unprofitable.

As a result, the Oilsand project was developed. The goal was to use nuclear explosives underground in the Athabasca region to generate heat and pressure that would cause the bituminous deposits to boil, reducing their viscosity so that conventional oil industry methods could be used to extract the oil.

The idea was that the explosion would turn the deposit into an oil lake. Initially, the project to stimulate the underground oil formations using this method was called “The Cauldron” and was developed by geologist Manley L. Natland. He was convinced that underground explosions were the most efficient way to generate the heat required to thin the viscous bitumen so it could be pumped out through conventional wells. The project was part of the American “Plowshare” operation, which explored various ways to use nuclear explosions for peaceful purposes.

However, over time, some experts began to question the viability of such a method. Pioneer of oil sands, Robert Fitzsimmons, wrote in the Edmonton Journal that the project’s author lacked knowledge of nuclear energy, and therefore could not be sure of the safety of the operation. Fitzsimmons suggested that there was a risk of turning the entire deposit into a burning hell, a mass of semi-glass or coke.

However, in 1959, the Federal Department of Mines approved the project, though by then it was renamed Oilsand. Three years later, Canada’s position changed: the country opposed nuclear testing. This shift, according to many historians, was influenced by the change in public perception of nuclear explosions after the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis – the confrontation between the USSR and the USA after the USSR secretly deployed nuclear missiles in Cuba in October 1962. For the first time in human history, the two superpowers found themselves under the threat of nuclear war. Thus, the Oilsand project was canceled.

Commercial Extraction

Commercial oil extraction from the Athabasca bituminous deposits began in 1967 with the opening of a plant in the Fort McMurray metropolitan area. The extraction was managed by the American company Sun Oil Company (later renamed Sunoco). The plant was opened at a cost of 240 million USD, with a daily capacity of 45,000 barrels (7,200 m³).

In general, the process of extracting oil from the sand is very expensive. To extract one barrel of crude oil, two tons of sand are needed. Investments in oil sands became profitable after 2000, when oil prices rose sharply.

Sunoco later left the oil business and became a retail distributor of gasoline. Extraction was actively taken over by Suncor Energy. In 2009, it bought the oil company Petro-Canada and became Canada’s largest oil company.

Environmental Impact

Extracting oil from oil sands has a huge impact on the environment. Both open-pit and underground extraction methods involve deforestation. Tailings ponds (facilities for storing radioactive, toxic, or other waste) contain toxins that can leak into groundwater or the Athabasca River. During extraction, sulfur oxides, nitrogen oxides, hydrocarbons, and fine particulates are released into the air.

Additionally, extracting and separating oil from the sands requires energy, and as a result, oil sands extraction releases more greenhouse gases than other forms of oil extraction. Because of all these reasons, oil sands are often referred to as an ecological threat. At the same time, this extraction remains a stable source of economic growth for Alberta.